Formula E Racing Can Lead to Future Innovations

Mechanical Engineering student Omkar Ligade, MS’23, fell in love with Formula E racing back in India which inspires him to build and improve the designs of the cars.

Formula E racing inspires this Northeastern engineer

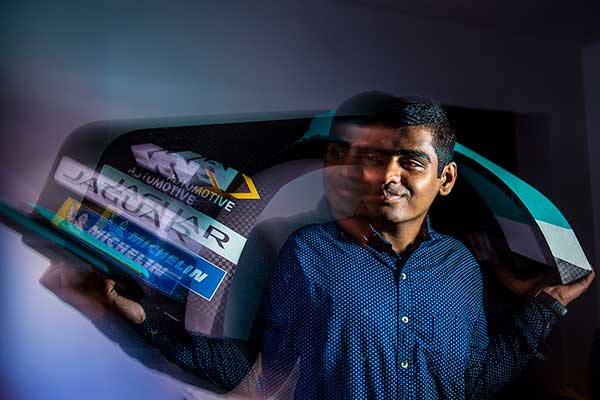

Omkar Ligude, a master’s student in engineering, came home with a souvenir fender after volunteering at the July 16 New York City E-Prix. Photo by Alyssa Stone/Northeastern University

Omkar Ligade, a mechanical engineering master’s student, was stationed at Turn 4 when the first crash happened. A sudden rainstorm had sent the electric cars sliding across the city streets of Brooklyn.

“The race leader lost traction and went into the side protection boards,” says Ligade. He was volunteering as a flagging and communication marshall at the July 16 New York City E-Prix when a pile-up of crashes resulted in an early conclusion to the race.

Ligade brought home a souvenir—a fender from a crashed Jaguar.

“Fortunately no one was hurt,” Ligade says. “The crashes weren’t actually loud because the rain reduced their speed, and the carbon fiber [chassis] is really good at absorbing the impact.”

Though electric cars are less noisy than traditional gas-powered racers, Ligade found the New York event to be very loud. “Very few people know about it because Formula E is in the early stages,” Ligade says. “But it’s going to have its boom within a few years.”

|

|

|

Omkar Ligude, a master’s student in mechanical engineering, led an undergraduate team in India that built three EVs from scratch and recently he served as a marshall at the Formula E race in New York City. Ligade, who treasures his Formula E souvenir, believes the sport is ready to rise in popularity. Photos by Alyssa Stone/Northeastern University

Formula E was launched in 2014 in alliance with the 73-year-old global Formula 1 circuit, whose growing U.S. audience has been driven by the Netflix reality series “Drive to Survive.” True to the spirit of electric vehicles, Formula E teams must balance the desire to win with the need to conserve energy as each car is provided with a limited battery for the 45-minute races.

Ligade fell in love with the sport as a mechanical engineering undergraduate at Pimpri Chinchwad College Of Engineering in his native India, where in 2016 he co-founded Team Solarium, a student club that designed and built an electric car annually over three years. The progression made Ligade proud.

“The third-year finished product was really lovely,” says Ligade, noting that its speed topped out at 80 kilometers per hour (50 mph).

Formula E creates innovations that can be passed onto consumer products. The newest racers feature enhanced regenerative front-mounted brakes that replenish the battery—a system so efficient that the cars no longer require a second set of hydraulic brakes in the rear.

“The racing department sits directly underneath the technical development department,” Allan McNish, Audi Sport’s Formula E team principal, told Time. “There is always the very close hand-in-hand relationship between what we do on the track and what actually comes on the road [for consumers].” Formula E is helping to change perceptions of electric vehicles as underperforming. The current racers top out at 280 kilometers per hour (almost 175mph), just 20 kmh behind Formula 1 cars, and their acceleration from zero to 100 kmh in 2.8 seconds rates only 0.2 seconds slower than gas-powered counterparts.

|

|

|

|

Ligade, who previously led an undergraduate team in India that built three electric vehicles from scratch, served as a flagging and communication marshall at the Formula E event in New York. Photos by Dennis Quiggle and Courtesy of Omkar Ligade

“I like that electric vehicles can generate energy,” Ligade says. “In gas-powered cars, once you’ve burned the petrol, you can’t get that fuel back.”

Instead of offering pit stops, Formula E offers “attack mode” zones on the edges of the track that trigger four minutes of increased power. The five most popular drivers—based on a pre-race vote by fans—receive additional power surges, a novelty that Ligade loves.

The evolution of electric vehicles continues to inspire Ligade amid his ongoing co-op with Hasbro, the Rhode Island-based toy manufacturer, where he is working as a reliability engineer.

“Omkar is always looking to better understand the ‘why’ in what we do, which is an essential trait of great engineers,” says his supervisor, Lee Tympanick, a senior reliability engineer for quality assurance at Hasbro. “He isn’t afraid to offer his perspective on a different approach to accomplish a task. He is also passionate about learning new things—procedures, equipment, products, skills—which tells me he wants to keep improving himself to be the best he can be.”

Will his love of Formula E drive Ligade to a career in electric vehicles?

“I’m really interested in designing anything,” he says. “Designing is the gateway to finding the solution to any problem. It helps you find a better way.”

by Ian Thomsen, News @ Northeastern