When Work is Play

Always driven to see how things worked, mechanical engineering student Amanda Vasconcelos, E’22, now uses those talents to build better toys while working on co-op at Hasbro.

She deconstructed robotic toys as a kid. Now she builds them for Hasbro.

Main photo: Mechanical engineering major Amanda Vasconcelos considers herself “one of the lucky people” to have always known what career she wanted. Now, she’s building animatronic toys as a co-op at toy-maker Hasbro. Photo by Ruby Wallau/Northeastern University

At seven years old, Amanda Vasconcelos’s future in engineering was evident—even if she didn’t know it just yet.

A curious young Vasconcelos liked to take apart her Baby Alive toy, a doll brand made by global toy-maker Hasbro that can move its mouth, eat, drink, and perform other life-like functions. She called it “performing surgery” on the doll, Vasconcelos says, “but I was really just interested in what inside them would make them move.”

As she got older, Vasconcelos continued to disassemble toys—the robotic ones, “the expensive toys,” she adds. “My mom was not pleased.”

But now, instead of deconstructing those toys, Vasconcelos, a third-year mechanical engineering major at Northeastern, is building new ones, figuring out how best to make them move herself.

Vasconcelos is working at Hasbro as a co-op in animatronics. “I could go back to my mom now and say, ‘See, I took them apart for a reason, and now it’s my job,’” Vasconcelos says.

|

|

|

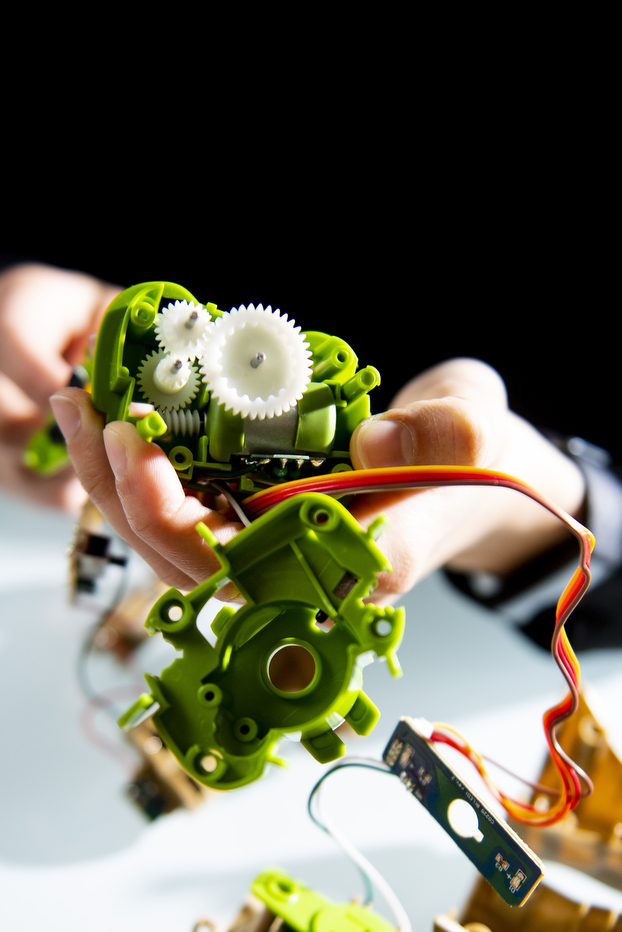

Vasconcelos liked to take apart her robotic toys as a child. Now, instead of deconstructing them, she’s building new ones herself. Photo by Ruby Wallau/Northeastern University

In her work, Vasconcelos figures out how best to design the mechanisms underlying an animatronic toy concept. The process starts virtually, as she creates a version of the toy in computer-aided design software. Then, it moves off the screen and into her hands. Vasconcelos 3D-prints or otherwise assembles the necessary parts and motors, and puts them together to make the prototype walk, talk, dance, or perform whatever other action intended. Vasconcelos then films that process to share with the rest of the team.

But the toy doesn’t look very much like what you’d buy in the store just yet. “We have to make something that works, and then we can see it moving and decide, ‘Do we like this? Is this going to sell? Does it do what we want it to do?’” Vasconcelos says.

“It was not a hard decision to be a mechanical engineer,” Vasconcelos says. Photo by Ruby Wallau/Northeastern University

Toys in various stages of development are scattered across Vasconcelos’ desk. Some have a head that looks like the actual toy with a much more mechanically appearing body. Others resemble toys even less. The aesthetics generally come later, she says, after the team decides on the mechanisms for the animatronic toys.

Vasconcelos has worked on toys that will be the next generation of existing brands at Hasbro, such as Playskool, Potato Head, Marvel, and Furreal Friends, as well as new concepts that have yet to be revealed to customers. All co-ops at Hasbro also get to create their own toy concepts in what is called the “Epic Project.” In teams of four or five, co-ops across the company have to pitch an idea for a toy by the end of their tenure. They consider design, marketing, cost, and all other aspects of bringing the idea of a toy to life on store shelves, and propose it to Hasbro. If the company likes the pitch, it might be selected to be produced and sold.

“It was not a hard decision to be a mechanical engineer,” Vasconcelos says. As a child, she loved building things and figuring out how to make them work. She even tried—unsuccessfully—to build a television from random items around the house. “I’m one of the lucky people who has actually known what I’m interested in for a long portion of my life,” she says.

Although Vasconcelos pursued her enduring interest in engineering and robotics in a high school robotics club and other endeavors, it wasn’t until 2019 that she realized her childhood curiosity about her animatronic toys specifically could lead to a career.

That summer, she worked as a student mentor in Northeastern’s summer engineering program for high school students, called the Pre-College Accelerate Programs. The group went on a tour at Hasbro that was hosted by the animatronics engineers.

That’s when it clicked. “This is incredible,” Vasconcelos recalls thinking. “This is exactly what I’m interested in for a co-op.”

The co-op experience at Hasbro has more than lived up to Vasconcelos’s expectations, she says. “It’s a lot more hands-on than I thought it would be. It’s really just getting in there, designing something, trying it out, and going from there,” she says. “I did not anticipate it would as much fun to work here.”

The job has also been empowering, Vasconcelos says. Previously, “I would see those mechanisms working in a toy or in class and wonder, ‘How did people even come up with that? How do you go from wanting the arm to rotate like this, how do you then work backwards to what you have to design to make that work?’” But now, that’s what Vasconcelos does every day. And that has fortified her focus on building a career in robotics.

That process of designing unique mechanisms on the computer and then creating a functional item in the real world particularly excites Vasconcelos. “It’s really amazing to be like, ‘Oh, I made that on my computer, and now I’m holding it. And now I’m going to put it together with motors and it’s going to do what I want it to do,’” she says. “It’s really satisfying as a process.”

“Even if I don’t end up in toys,” Vasconcelos says, “I like that what I’m working on is going to go out into the world and be a part of people’s lives.”

by Eva Botkin-Kowacki, News @ Northeastern